Container Runtimes

This section will provide you with an overview of container runtimes.

What is a container runtime ?

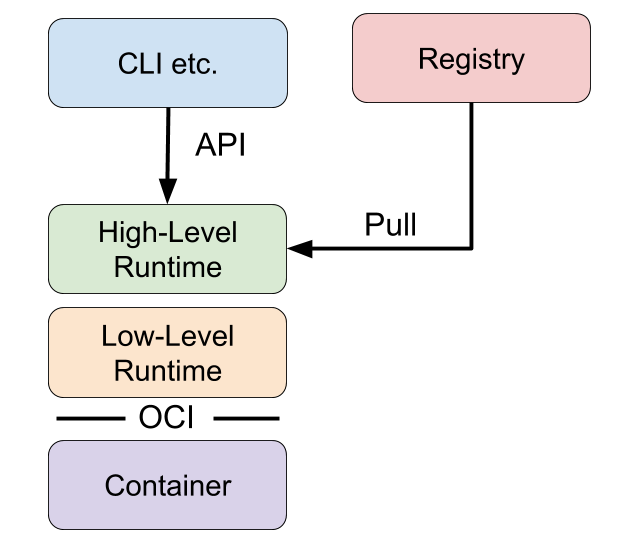

A container runtime is the foundational software that allows containers to operate within a host system. Container runtime is responsible for everything from pulling container images from a container registry and managing their life cycle to running the containers on your system.

Functionality and responsibilities

Understanding core functionalities and responsibilities is vital to appreciating how container runtimes facilitate the seamless execution and management of containers. Generally, a container runtime do the following jobs:

Execution of containers

Container runtimes primarily execute containers through a multi-step process. As a first step, this process begins by creating containers and initializing their environment based on a container image that contains the application and its dependencies. Following creation, the runtime runs the containers, starts the application, and ensures its proper function. Additionally, the runtime manages containers’ life cycles, which involves monitoring their health, restarting them if they fail, and cleaning up resources once the containers are no longer in use.

Interaction with the host operating system

Container runtimes interact closely with the host operating system. They leverage various features of the OS, like namespaces and cgroups, to isolate and manage resources for each container. This isolation guarantees that processes inside a container are unable to disrupt the host or other containers, preserving a secure and stable environment.

Resource allocation and management

Container runtimes are an essential part of resource management because they allocate and regulate CPU, memory, and I/O for each container to prevent resource monopolization, especially in multi-tenant environments. The way container runtimes smoothly handle the running, life cycle, and interaction of containers with the host OS is key to why containerization is such a big part of today’s software development landscape.

Low-Level and High-Level Container Runtimes

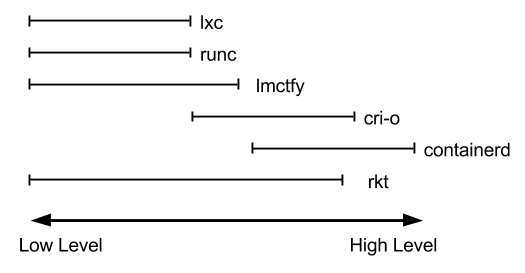

Talking of container runtimes, a list of examples might come to mind: runc, lxc, lmctfy, Docker (containerd), rkt, cri-o. Each of these is built for different situations and implements different features. Some, like containerd and cri-o, actually use runc to run the container but implement image management and APIs on top. You can think of these features – which include image transport, image management, image unpacking, and APIs – as high-level features as compared to runc’s low-level implementation.

With that in mind you can see that the container runtime space is fairly complicated. Each runtime covers different parts of this low-level to high-level spectrum. Here is a very subjective diagram:

Therefore, for practical purposes, actual container runtimes that focus on just running containers are usually referred to as “low-level container runtimes”. Runtimes that support more high-level features, like image management and gRPC/Web APIs, are usually referred to as “high-level container tools”, “high-level container runtimes” or usually just “container runtimes”. This section will refer to them as “high-level container runtimes”. It’s important to note that low-level runtimes and high-level runtimes are fundamentally different things that solve different problems.

Typically, developers who want to run apps in containers will need more than just the features that low-level runtimes provide. They need APIs and features around image formats, image management, and sharing images. These features are provided by high-level runtimes. Low-level runtimes just don’t provide enough features for this everyday use. For that reason those that will actually use low-level runtimes would only be developers who implement higher level runtimes, and tools for containers.

Developers who implement low-level runtimes will say that higher level runtimes like containerd and cri-o are not actually container runtimes, as from their perspective they outsource the implementation of running a container to runc. However, from the user’s perspective, they are a singular component that provides the ability to run containers.

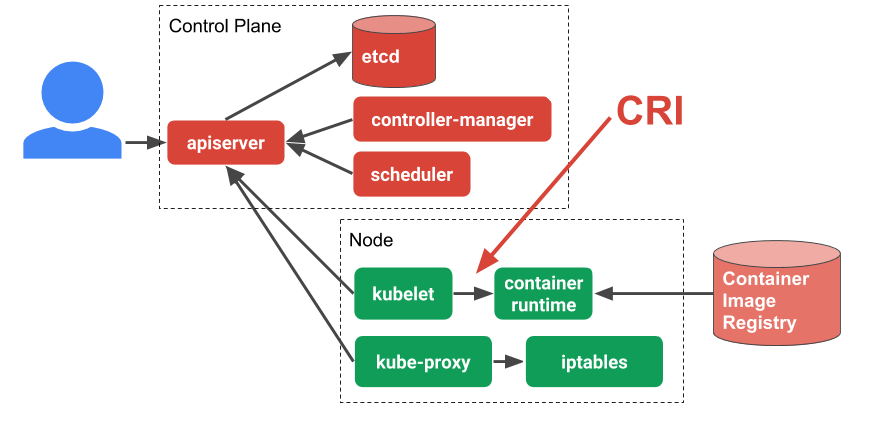

Kubernetes container runtimes

Kubernetes runtimes are high-level container runtimes that support the Container Runtime Interface (CRI). CRI was introduced in Kubernetes 1.5 and acts as a bridge between the kubelet and the container runtime. High-level container runtimes that want to integrate with Kubernetes are expected to implement CRI. The runtime is expected to handle the management of images and to support Kubernetes pods, as well as manage the individual containers, and therefore, is considered a high-level runtime by the categorisation above.

In order to understand more about CRI it’s worth taking once more look at the overall Kubernetes architecture. The kubelet is an agent that sits on each worker node in the Kubernetes cluster. The kubelet is responsible for managing the container workloads for its node. When it comes to actually run the workload, the kubelet uses CRI to communicate with the container runtime running on that same node. In this way CRI is simply an abstraction layer or API that allows you to switch out container runtime implementations instead of having them built into the kubelet.

Below are some CRI runtimes that can be used with Kubernetes:

Docker

Docker is one of the first open source container runtimes. It was developed by the platform-as-a-service company dotCloud, and was used to run their users’ web applications in containers.

Docker is a container runtime that incorporates building, packaging, sharing, and running containers. Docker has a client/server architecture and was originally built as a monolithic daemon, dockerd, and the docker client application. The daemon provided most of the logic of building containers, managing the images, and running containers, along with an API. The command line client could be run to send commands and to get information from the daemon.

Docker originally implemented both high-level and low-level runtime features, but those pieces have since been broken out into separate projects as runc and containerd. Docker now consists of the dockerd daemon, and the docker-containerd daemon along with docker-runc. docker-containerd and docker-runc are just Docker packaged versions of vanilla containerd and runc.

dockerd provides features such as building images, and dockerd uses docker-containerd to provide features such as image management and running containers. For instance, Docker’s build step is actually just some logic that interprets a Dockerfile, runs the necessary commands in a container using containerd, and saves the resulting container file system as an image.

containerd

containerd is a high-level runtime that was split off from Docker. Like runc, which was broken off as the low-level runtime piece, containerd was broken off as the high-level runtime piece of Docker. containerd implements downloading images, managing them, and running containers from images. When it needs to run a container it unpacks the image into an OCI runtime bundle and shells out to runc to run it.

containerd also provides an API and client application that can be used to interact with it. The containerd command line client is ctr.

ctr can be used to tell containerd to pull a container image:

sudo ctr images pull docker.io/library/redis:latest

List the images you have:

sudo ctr images list

Run a container based on an image:

sudo ctr container create docker.io/library/redis:latest redis

List the running containers:

sudo ctr container list

Stop the container:

sudo ctr container delete redis

These commands are similar to how a user interacts with Docker. However, in contrast with Docker, containerd is focused solely on running containers, so it does not provide a mechanism for building containers. Docker was focused on end-user and developer use cases, whereas containerd is focused on operational use cases, such as running containers on servers. Tasks such as building container images are left to other tools.

cri-o

cri-o is a lightweight CRI runtime made as a Kubernetes specific high-level runtime. It supports the management of OCI compatible images and pulls from any OCI compatible image registry. It supports runc and Clear Containers as low-level runtimes. It supports other OCI compatible low-level runtimes in theory, but relies on compatibility with the runc OCI command line interface, so in practice it isn’t as flexible as containerd’s shim API.

cri-o’s endpoint is at /var/run/crio/crio.sock by default so you can configure crictl like so.

cat <<EOF | sudo tee /etc/crictl.yaml

runtime-endpoint: unix:///var/run/crio/crio.sock

EOF

Interacting with CRI

We can interact with a CRI runtime directly using the crictl tool. crictl lets us send gRPC messages to a CRI runtime directly from the command line. We can use this to debug and test out CRI implementations without starting up a full-blown kubelet or Kubernetes cluster. You can get it by downloading a crictl binary from the cri-tools releases page on GitHub.

You can configure crictl by creating a configuration file under /etc/crictl.yaml. Here you should specify the runtime’s gRPC endpoint as either a Unix socket file (unix:///path/to/file) or a TCP endpoint (tcp://<host>:<port>). We will use containerd for this example:

cat <<EOF | sudo tee /etc/crictl.yaml

runtime-endpoint: unix:///run/`containerd`/`containerd`.sock

EOF

Or you can specify the runtime endpoint on each command line execution:

crictl --runtime-endpoint unix:///run/`containerd`/`containerd`.sock …

Let’s run a pod with a single container with crictl. First you would tell the runtime to pull the nginx image you need since you can’t start a container without the image stored locally.

sudo crictl pull nginx

Next create a Pod creation request. You do this as a JSON file.

cat <<EOF | tee sandbox.json

{

"metadata": {

"name": "nginx-sandbox",

"namespace": "default",

"attempt": 1,

"uid": "hdishd83djaidwnduwk28bcsb"

},

"linux": {

},

"log_directory": "/tmp"

}

EOF

And then create the pod sandbox. We will store the ID of the sandbox as SANDBOX_ID.

SANDBOX_ID=$(sudo crictl runp --runtime runsc sandbox.json)

Next we will create a container creation request in a JSON file.

cat <<EOF | tee container.json

{

"metadata": {

"name": "nginx"

},

"image":{

"image": "nginx"

},

"log_path":"nginx.0.log",

"linux": {

}

}

EOF

We can then create and start the container inside the Pod we created earlier.

CONTAINER_ID=$(sudo crictl create ${SANDBOX_ID} container.json sandbox.json)

sudo crictl start ${CONTAINER_ID}

You can inspect the running pod

sudo crictl inspectp ${SANDBOX_ID}

… and the running container:

sudo crictl inspect ${CONTAINER_ID}

Clean up by stopping and deleting the container:

sudo crictl stop ${CONTAINER_ID}

sudo crictl rm ${CONTAINER_ID}

And then stop and delete the Pod:

sudo crictl stopp ${SANDBOX_ID}

sudo crictl rmp ${SANDBOX_ID}